Listen here: https://anchor.fm/cj123/episodes/18th-Century-Podcast-Episode-21-Spycraft-e86oi3/a-auf07g

Summary

In today’s episode, we’ll be going over spycraft in the 18th Century. We’ll cover some techniques spies would use to conceal their messages, and some notable spies from the 18th Century like Nathan Hale. We’ll also discuss some spy activity during Benjamin Franklin’s time in Paris. You don’t want to miss this one!

Script

INTRO

Welcome back to the 18th Century Podcast. I am your host, Cj. In today’s episode, we’ll be going over spycraft in the 18th Century. If you’d like to read the script for this episode and its citations, go to 18thcentury.home.blog that’s 1, 8, t h, century dot home dot blog. Type the numbers don’t spell them. Let’s kick things off by talking about a general overview of spycraft in the 18th Century.

PART 1 SPYCRAFT

Spying was frowned upon in the 18th Century. It could lead to a death sentence. There was a view that spying was ungentlemanly. It was an activity that was used but frowned upon. Though States may not openly admit that they used spies, spies were vital in times of war. There were no central intelligence organizations like there are today, but agents or rings were formed when necessary. Perhaps the most famous spy ring in the 18th Century was the Culper Spy Ring, which I did read a few of their letters, however poorly, a couple of episodes ago. I’d recommend checking out the blog post for that episode so you can read the letters yourself. I won’t be going into the Culper Ring today, as that will be a future episode in and of itself. Though spies were used, it was more common for a military to gain intelligence from local sources about their enemy. This could be through local newspapers, rumors, or gossip. People like to talk and information travels. But between spies, they would communicate mainly through letters and coded messages. Ciphers were a popular method of concealing information. Books were sometimes written to decipher the messages. These books would have typically been within the ring only. Another method which also dates back centuries was invisible ink. For example, during the American Revolution, an invisible ink was made by mixing ferrous sulfate and water. The spy would write the hidden message between lines of a letter and then pass it off. To read the message heat or another chemical could be applied. One such chemical which could bring forth the message was sodium carbonate. Now, a British method of transferring information, which could have been used by other States as well, was hidden messages. Hidden messages would be written on small pieces of paper and concealed in an object, which a courier could transfer. One method which I have seen before but I forgot about was masked messages. A masked message was when a message would be concealed in a letter that only could be read if a specially designed shaped template was placed over the letter. Spies have been used for centuries before and centuries after, but I think it’s time we take a look into a small story of spies in France during the second half of the 1770s.

PART 2 SPIES NESTLED IN PARIS

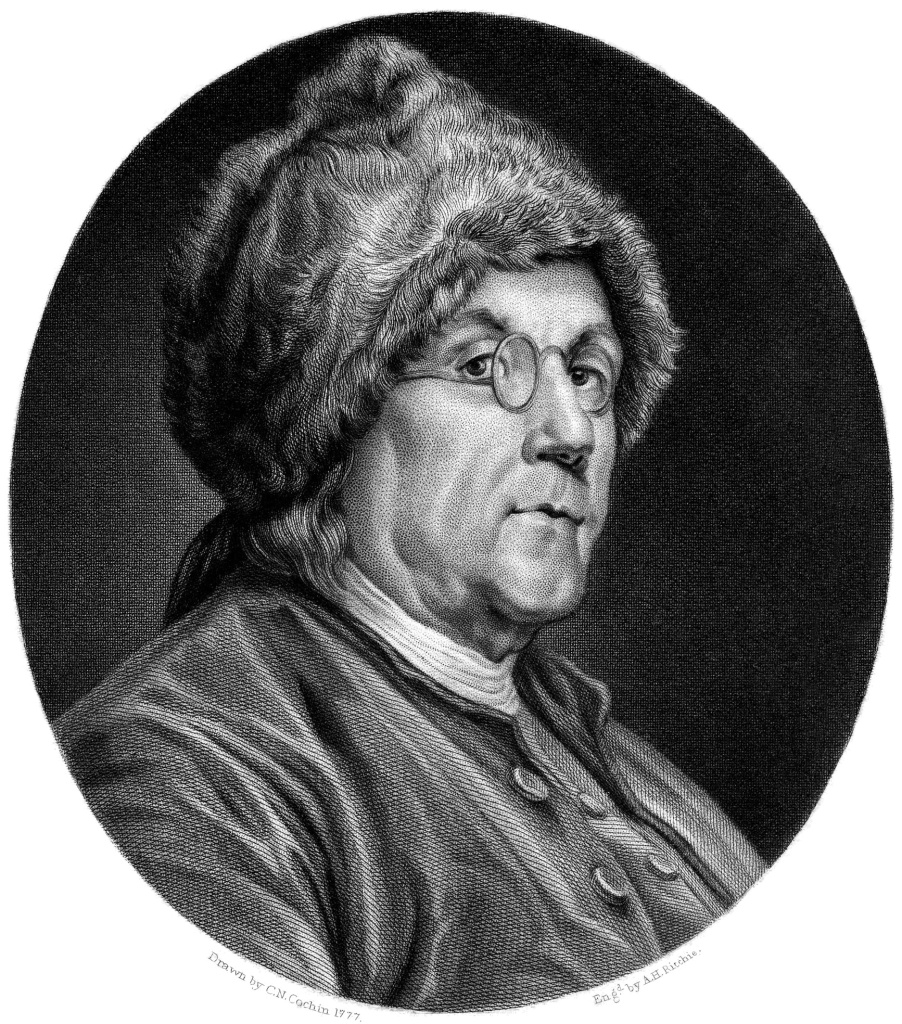

This section will be covering part of the American Revolution, and I know I’ve talked about doing my American Revolution series on the podcast for a few episodes. It’s coming… eventually. But I do want to share a small tale concerning spies and Paris during this period. Our tale begins in 1776 when the new Congress of the United States sends Benjamin Franklin to France as a diplomat. His mission is to gain French support for the American Cause. I think it goes without saying how famous Benjamin Franklin was in Paris. The French loved him, and I’ll dive deeper into this when I do a bio on Benjamin Franklin. However, there were still some under the table dealings Franklin did while in France. Franklin had amassed a connection of friends in France and Agents working under him. Franklin would launch a series of schemes while also conducting diplomacy. One such instance was a successful piece of propaganda against the British on their turf. One ploy of propaganda was giving false newspaper stories of Britain’s Native American allies which stipulated that the Natives were committing horrendous acts on the frontier. The ploy would pay off as it caused a further division in Parliament. Franklin’s agents would amass a bounty of British Naval movements. I think this goes without saying how well connected he truly was. The British Ambassador to France was quoted as saying about Franklin, quote, “veteran of mischief,” unquote. Franklin was clever, but one thing he never found out during his time in Paris, was that his then Secretary, Edward Bancroft, was an agent for the British. Edward would write the intelligence on Franklin in invisible ink, then he would leave it at a dead drop where Paul Wentworth, the man in charge of British espionage in Paris, would pick it up. The information gathered by Edward would successfully make it’s way to the direct hands of King George III. However, the information collected on Franklin was mostly in vain. King George III, for the most part, dismissed the information collected. Franklin did come to suspect there was a mole in his midst and he would on occasion, send false information as a way to trap the British Agent. He never did figure out it was his own Secretary. Now, the French had their very own well-connected spy ring in their Capitol. The French would spy on citizens and foreigners alike. The French agents would gather their information through a plethora of ways, among which were, gossip, and pillow talk after relations. It goes without saying, the French had spies placed on Franklin. Franklin, of course, was aware he was being watched. He knew both about the British and the French, though he may not have known the exact identity of all the spies placed on him. After the Americans claimed victory of the Battle of Saratoga, the British were considering to find a way to reconcile with the Americans. Franklin became aware of this and hatched a plan which would help encourage the French to support the American cause. Though the French were not in the conflict as of yet, a prolonged conflict could have benefited the French over their most hated adversary, the British. Franklin pretended he was interested in talking with the British. Possibly, he implied opening a dialogue with them. This was discovered by French agents, and the information was passed along. The French panicked. They hastened for a deal giving support to the Americans. Through careful maneuvering, and playing the agents on him, Franklin’s plan was realized. Now, we’re going to take a short break, and when we come back for the second half of this episode, we’re going to take a look at some notable spies in the 18th Century. Don’t go away.

PART 3 PROMINENT SPIES

Welcome back. We’ll continue the second half of today’s show discussing some of the most prominent spies in the 18th Century. I’m going to start this off with one of the most famous spies in the 18th Century Nathan Hale. Nathan Hale was a graduate of Yale and a schoolteacher from Connecticut. When the American War for Independence broke out Nathan joined the Connecticut regiment in 1775. He would gain the rank of Captain. During the early phases of the War, Washington needed intelligence on the British. Young Nathan volunteered to go and spy on their adversary on September 10th, 1776. He would disguise himself as a Dutch Schoolmaster and sneak past British lines on Long Island. Hale would spend the next few days collecting intelligence on British troop movements. On September 21st, Hale attempted to cross back to American lines, but he was captured by the British. Hale would be interrogated by British General William Howe. General Howe would discover incriminating documents on Hale’s person. General Howe ordered the execution of Hale for the following morning. Nathan Hale would receive no trail. The 21-year-old marched to the gallows, and purportedly his final words were, quote, “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country,” unquote. Hale would go down as one of the most famous spies in 18th Century history, even though he failed his mission and had no training or experience in spycraft.

Let’s transition to a successful spy, one over in Europe, a French spy named, Charles Théveneau de Morande. I will hence refer to him as Charles. Charles was a lawyer’s son, and he served in the Seven Years War. After the Seven Years War, Charles made his way to Paris where he would indulge himself in Vice. Things would get heated for him and he fled Paris in 1770 to London to avoid being arrested. In London, he would print pamphlets attacking King Louis XV’s mistress. Louis XV was furious with Charles’s activities. He wanted the man extradited or kidnaped if possible, but his attempts bore no fruit. When initial revenge attempts failed, the King decided to attempt another plan. He plotted to turn Charles into a spy, and he sent Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais to London to recruit Charles. Pierre-Augustin was in disgrace at the time from losing two court cases in the 1770s. Seeking redemption, Pierre-Augustin traveled to London to recruit Charles. The French Foreign Minister, Charles de Vergennes, also saw our Charles as someone worth investing in. Charles had a knack for uncovering secrets and publishing them in pamphlets, and his outspokenness against the French King would add a layer of protection against British suspicion. During the American War of Independence, Charles kept track of ship movements out of British ports, and very successfully at that. He continued his service spying on the British after the war as well. He would go on and recruit high up engineers to his side. Charles became the editor of a prominent French newspaper in London, Courier de l’Europe. This new position would further give him credence for information gathering. The paper was a massive hit across Europe, but not so much in Parliament. The British Parliament viewed it as a sort of open espionage during the American War of Independence. The allegations that the paper was, in fact, a form of espionage were basically true. The British eventually banned the exportation of the paper. But it’s Naval Officer and Enturepenure, Samuel Swinton, smuggled it out. Samuel was a British spy and used the paper as a means to enter France where he would conduct operations on the Americans and French. All the while Charles was printing hidden messages in paragraphs in the paper which were codded for French intelligence. During the American Revolution, The French helped set up a ring with Charles were he would have multiple couriers in a sort of loose network as not to arouse suspicion. The British did suspect Charles as an agent for France, but they never gathered proof. Charles would remain in Great Britain until 1791 when he made his return to France.

Our final spy for today comes from Sweden. Eva Löwen was born in 1743 and the daughter of the Governor-General. Her family was well politically connected. When her father was appointed as the Governor-General, the family moved. At their new home, Eva would meet her future husband Fredrik Ribbing. Fredrik was politically well connected himself and was close to the Royal couple. Eva would find herself in the heart of Swedish politics in the mid-1760s. Eva would become popular in Swedish high society. She was characterized as witty, and admirable, but also renowned for her… escapades in the private company of others. I trust you understand what I’m getting at. She became a lover of the French Ambassador to Sweden, Louis Auguste Le Tonnelier de Breteuil. Gustav III attempted to initiate a relationship with Eva, but she rejected his advances. She had other relations with high ranking men in Swedish society, and this may have gained the interest of the French. In the years before Gustav III’s coup, she was on a list of recipients receiving a pension from the French Government. After Gustav III’s successful coup and coronation of 1772, Eva grew closer with him as a friend and they spent their time in grand conversation. Everything would fall apart with the death of Eva’s husband in 1783. Eva would first move in with Gustaf Macklean, a person she previously had a connection to. Gustav III began to fall out of favor. Eva’s son became a part of an assassination plot to kill King Gustav III. Her son had influence from what was occurring in France at the time. After the assassination of Gustav III, he was sentenced to death, but received a pardon and was expelled from Sweden and stripped of nobility. Eva and Gustaf Macklean accompanied her son first to Paris, and then to Switzerland. Eva and Gustaf would marry in 1796 and moved into a Manor in Sweden. Eva died at home in 1813.

OUTRO

This brings us to the end of this week’s episode. Spies and their history is certainly a fascinating topic. I learned a few things this week which I did not expect, and I hope you did as well. The script and citations for this episode and all other episodes can be found at 18thcentury.home.blog that’s 1, 8, t h, century dot home dot blog. Type the numbers don’t spell them. If you’d like to support the show, please share it and leave a review. I’ve been your host Cj, and thank you for listening to this episode of the 18th Century Podcast.

CITATIONS

“Spy Techniques of the Revolutionary War.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/spying-and-espionage/spy-techniques-of-the-revolutionary-war/.

Crews, Ed. “Spies and Scouts, Secret Writing, and Sympathetic Citizens.” Spies and Scouts, Secret Writing, and Sympathetic Citizens : The Colonial Williamsburg Official History & Citizenship Site, 2004, https://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Summer04/spies.cfm.

HistoryExtraAdmin. “18th Century Espionage: the French Spy in London.” HistoryExtra, 10 Oct. 2018, https://www.historyextra.com/period/georgian/18th-century-espionage-the-french-spy-in-london/.

“Nathan Hale Is Executed by the British for Spying.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 13 Nov. 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/patriot-executed-for-spying.

Eva Helena Löwen, http://www.skbl.se/sv/artikel/EvaLowen, Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon (article by Brita Planck), retrieved 2019-10-25.